The United States is facing an urgent crisis: a significant shortage of behavioral health professionals that leaves countless individuals without the care they desperately need (Bishop et al., 2024). In this landscape, optimizing the existing workforce is not merely a tactical choice; it is a strategic necessity. One promising avenue for this optimization lies within primary care settings, where the unique needs of midlife women navigating the tumultuous menopausal transition are often overlooked.

Midlife women often navigate a challenging landscape of mental health symptoms, including anxiety, mood swings, cognitive changes, and elevated stress levels. The complexities of these issues are frequently overlooked or misattributed to other medical conditions. This is where the role of the Behavioral Health Consultant (BHC) becomes indispensable. Within the framework of the Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) integrated care model, BHCs serve as essential liaisons between mental health and primary care services.

The Problem: A Menopause Misdiagnosis Epidemic

The symptoms of the perimenopausal and menopausal transition—which can span a decade, are notoriously broad and often mimic primary psychiatric disorders. Leading clinical bodies note that women with no history of mental illness may experience new-onset depression and anxiety during this time due to fluctuating estrogen levels (Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health [MGH], n.d.). These symptoms include intense mood swings, irritability, sleep disturbance, and concentration difficulties often described as “brain fog” (Dementia UK, n.d.; Greene, 1998).

In the traditional, time-crunched primary care visit, these complaints are often addressed by focusing solely on the mental health component (Cleveland Clinic, n.d.). A woman reports low mood and poor sleep, and the busy Primary Care Provider (PCP) or OB/GYN may initiate a script for an antidepressant without taking the detailed psychosocial and hormonal history needed for an accurate differential diagnosis. This practice leads to delayed detection and inadequate treatment.

BHCs: The Workforce Innovation in Triage

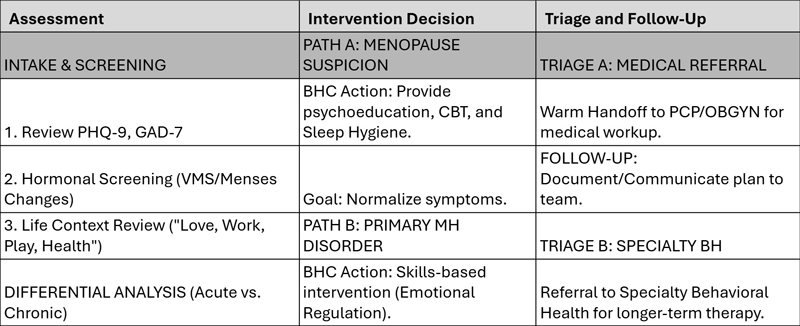

The BHC’s expertise in brief, focused assessment and differentiation is the perfect solution to this clinical challenge. Operating under a consultation model, the BHC is tasked not with traditional long-term therapy, but with rapid assessment, behavioral intervention, and effective triage (Robinson & Reiter, 2016).

Targeted Assessment and Differentiation

When a midlife woman presents to the integrated care clinic with symptoms like anxiety or insomnia, the BHC’s workflow is designed to quickly differentiate the likely cause. In addition to standard screening tools (PHQ-9 and GAD-7), the BHC can incorporate simple, validated screeners like the Greene Climacteric Scale or targeted questions regarding vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes, night sweats) and menstrual history.

Psychoeducation and Immediate Intervention

Once a hormonal component is suspected, the BHC immediately provides psychoeducation, normalizing the experience and reframing the symptoms from a mental health deficit to a hormonal transition. Furthermore, the BHC can implement evidence-based behavioral strategies within the same visit:

- Sleep Hygiene: Targeting insomnia related to night sweats.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Hot Flashes: A validated intervention to reduce the impact and severity of vasomotor symptoms (Hickey et al., 2022).

These interventions offer immediate relief while the patient awaits a specialized medical follow-up, thereby embodying whole-person care.

Upskilling for Emerging Roles

To maximize the BHC’s effectiveness in this crucial area, there must be a deliberate effort to upskill the existing workforce. While many BHCs are skilled in depression and anxiety, training programs should embed competencies specific to women’s health throughout the life cycle, including understanding neurobiological mechanisms and familiarity with menopausal treatments.

By investing in this specialized training, health systems transform their BHCs into clinical experts who not only screen for general mental health issues but also serve as the clinic’s front-line specialists for midlife women’s health. This strategic investment is a practical solution to the behavioral health workforce challenge, aligning with national efforts to expand access and quality of care (Bishop et al., 2024).

Essential Resources for BHCs and Patients

As BHCs often serve as educational resource brokers, having a curated list of reliable, evidence-based sources is vital for supporting patient self-management and facilitating informed dialogue with the medical team.

Conclusion

The integration of BHCs into the primary care system is not just beneficial; it is vital. The BHC in integrated care is more than just a therapist; they are a sophisticated triage specialist and educator. Leveraging their role to “unmask” menopause from generalized mood disorder is a powerful example of workforce innovation that yields better diagnosis, targeted treatment, and ultimately, superior patient outcomes.

Kim Hunter-Bryant, MA, LCSW, PMH-C, serves as the Director of Women’s Health & Wellness and a Behavioral Health Consultant at Covenant House Health Services. An advocate for workforce innovation in integrated care, she specializes in the intersection of behavioral health and women’s midlife transitions. Her clinical work focuses on “unmasking” menopausal symptoms in primary care to ensure accurate diagnosis and holistic treatment. For more information, contact kbryant@covenanthousehealth.org or visit Kim’s LinkedIn Profile.

References

Bishop, T. F., Seixas, A., & Pincus, H. A. (2024, February 8). Understanding the U.S. behavioral health workforce shortage. The Commonwealth Fund. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2024/feb/understanding-us-behavioral-health-workforce-shortage

Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Perimenopause: Age, stages, signs, symptoms & treatment. my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21608-perimenopause

Dementia UK. (n.d.). Young onset dementia: Perimenopause and menopause. https://www.dementiauk.org/information-and-support/young-onset-dementia/young-onset-dementia-perimenopause-and-menopause/

Greene, J. G. (1998). The climacteric scale. Maturitas, 29(2), 143–155.

Hickey, M., Szabo, R., Hayes, R., & Chin, J. (2022). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy for vasomotor symptoms in women with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas, 161, 31–37.

Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health. (n.d.). Psychiatric symptoms during menopause. https://womensmentalhealth.org/specialty-clinics/menopausal-symptoms/

Robinson, P. J., & Reiter, J. T. (2016). Behavioral consultation and primary care: A guide to integrating services (2nd ed.). Springer.