Postpartum depression (PPD)—the most common perinatal mood and anxiety disorder—is a debilitating condition affecting at least one in eight people who give birth. PPD is more than just the “baby blues.” It is a more severe mood disorder that can last for many months. PPD may impair a person’s ability to function, care for their baby, or maintain their health and relationships. Despite longstanding screening recommendations and available treatments, postpartum depression remains underdiagnosed and undertreated, particularly for marginalized populations.

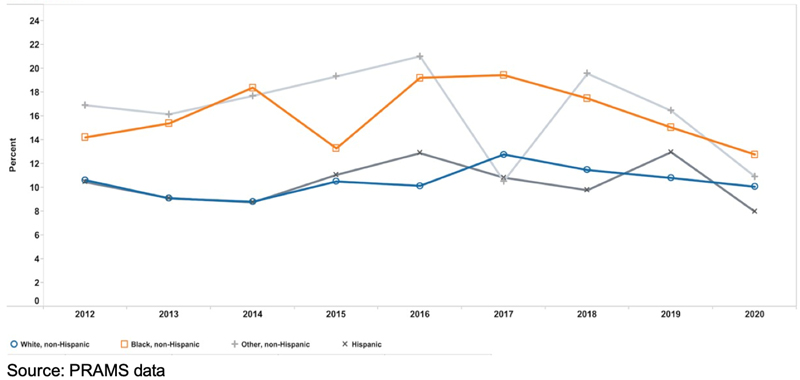

Figure 1. Percentage of women reporting depressive symptoms after giving birth, by race and ethnicity (NYS, 2012-2020)

Postpartum Depression in New York State

A recent legislatively mandated report from the New York State (NYS) Office of Mental Health (OMH) and Department of Health (DOH) provides a review of postpartum depression prevalence, screening, and risk factors in NYS. Its findings expose disparities in prevalence as well as gaps in postpartum screening and care, and opportunities for improvement.

The report relies heavily on PRAMS (Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System) data for estimates of PPD prevalence, screening, and provider identification. The CDC-sponsored PRAMS has been a valuable population-based risk factor surveillance program since the 1980s, surveying a representative sample of individuals who recently delivered a live-born infant, asking respondents about their experiences before, during, and after pregnancy.

According to NYS PRAMS data for 2020 (the most recent year available at the time of OMH-DOH report publication), roughly 10% of postpartum New Yorkers reported depressive symptoms. Consistently since 2012, higher percentages of self-reported PPD have been seen among racial and ethnic minoritized populations (see Figure 1) and among people of lower socioeconomic status.

Of the New Yorkers reporting PPD in 2020, only 34% indicated that they were told by a healthcare provider that they had depression—an alarming gap that signals missed opportunities for care.

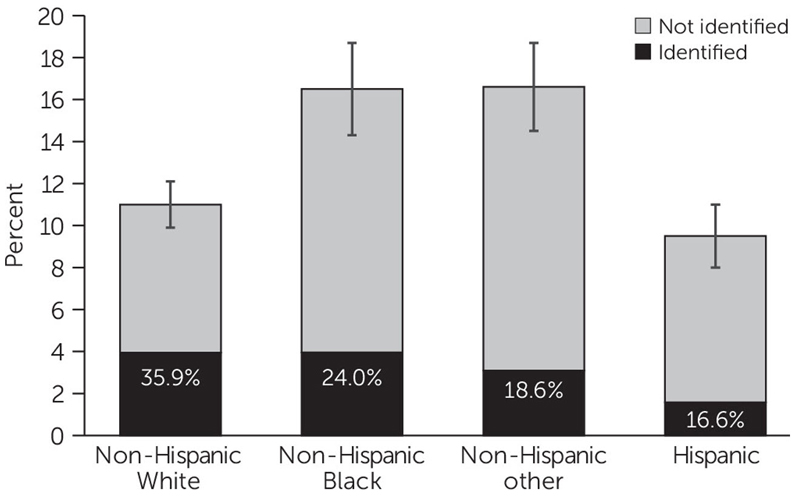

A recent analysis of PRAMS data from the years 2017-2022, published in the journal Psychiatric Services, allowed for a deeper exploration, examining this discrepancy by race and ethnicity (Figure 2). Among over 12,500 New Yorkers who had recently given birth, self-reported depressive symptoms were significantly higher for those identifying as non-Hispanic Black (17%) or non-Hispanic “other” (17%) compared to non-Hispanic White (11%) and Hispanic (10%) individuals. Provider identification of PPD among depressed individuals was even more skewed: Just 17% of Hispanic respondents and 19% of non-Hispanic “other” respondents who self-reported PPD symptoms said a provider had diagnosed them, compared to 36% of non-Hispanic White respondents.

Figure 2. Percentage of respondents (N=12,541) reporting postpartum depressive symptoms who also report being told by a health care provider that they had postpartum depression1

1. Data were from the New York State Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2017–2022. Percentages are weighted to represent New York State’s demographic composition. “Non-Hispanic other” includes PRAMS respondents identifying as American Indian, Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Hawaiian, other Asian, other race, or mixed race; 84% of this group was non-Hispanic Asian. Small sample sizes within this group prevented deeper—and much-needed—analysis. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Note: Figure 2 is taken from Ehntholt et al. Psychiatric Services 2025. In original publication, it is labelled Figure 1.

This mismatch between symptom reporting and clinical identification suggests systemic shortcomings in how PPD is assessed and might reflect broader social and structural factors, including socioeconomic status, access to care, provider bias, and historic mistrust in the healthcare system.

Disparities in Postpartum Mental Health Care

This analysis of NYS PRAMS data also exposes inequities in postpartum mental health care by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status in New York State. For example, Black and Hispanic women in the State were less likely than their White counterparts to receive postpartum checkups in 2020—a key opportunity for depression screening. Only 80% of non-Hispanic Black and 78% of Hispanic postpartum New Yorkers reported having such a checkup, compared to 91% of non-Hispanic White individuals. Postpartum New Yorkers who were unmarried, insured by Medicaid, or had attained less than a high school education were also less likely to report having a postpartum check-up.

Even among those diagnosed with depression, follow-up care was inconsistent. In 2020, just 55% of those diagnosed reported receiving counseling. White individuals were much more likely to report using medication to treat postpartum depression (71%) than were their Hispanic peers (38%).

Challenges with Screening Tools

The report identified that postpartum individuals in New York—and nationally—are not universally screened using standardized tools. Among postpartum New Yorkers who reported receiving a postpartum checkup in 2020, 82% reported being asked about depression at that visit, a number in line with the CDC’s national estimate for PPD screening. But this is likely an overestimate of how many individuals receive robust screening with a validated instrument, as this survey question serves as a proxy for being screened.

While organizations like the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommend PPD screening, current guidelines across entities lack clarity and consistency on how, when, and by whom screening should be performed. This has led to significant variation in practice and inequitable implementation of screening.

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) are two widely used tools. Both have been validated across diverse populations, but the OMH-DOH report notes that challenges remain. It is critical that screening instruments be tested and updated as needed for the unique subgroups of all New Yorkers, as language barriers, literacy, and cultural norms can affect how questions are interpreted and answered. The report strongly recommends that validated PPD screening tools be paired with assessments of social determinants of health (SDOH), which powerfully influence maternal mental health and well-being.

Social and Structural Determinants of Risk

The report highlights the many non-clinical factors that elevate risk for PPD, such as stressors like food insecurity, housing instability, low-quality sleep, intimate partner violence, and limited access to transportation or childcare.

Particularly high-risk groups include:

- Young parents

- LGBTQ+ individuals

- People with a history of mental illness

- Immigrant and refugee populations

- Those experiencing relationship or financial stress

New York State’s PRAMS data further demonstrate that postpartum people covered by Medicaid or with lower education levels consistently report higher rates of depressive symptoms, yet are less likely to be diagnosed or treated. For instance, in 2019, self-reported PPD was more than twice as common among those without a high school diploma compared to those with more than a high school education (23% vs. 11%).

Recommendations

In light of these and other findings, the NYS report offers a series of recommendations aimed at standardizing, expanding, and improving postpartum screening and care:

- Screening and Follow-up: Incorporate validated mental health screening tools into routine care from preconception through one year postpartum—not just immediately after birth. Include other perinatal mood and anxiety disorders beyond PPD. Screen for basic social needs using validated tools, including for housing, food, social support, intimate partner violence, and barriers to accessing care.

- Provider Training: Enhance training in cultural competence, implicit bias, trauma-informed care, and communication around mental health and substance use to reduce stigma and improve equity.

- Access to Treatment for Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders and to Resources to Meet Social Needs: Explore ways to improve pathways to care by increasing access and decreasing barriers to services and supports, including through partnerships with other state agencies.

- Reimbursement: Ensure adequate technical support and reimbursement for screening, education, and brief intervention to incentivize greater uptake by primary care and pediatric providers.

- Research: Collaborate with researchers to refine existing screening tools for cultural relevance and study technology-based solutions, like mobile phone-based screenings, which could reach more postpartum individuals in real time. Improve data collection systems to better capture subgroup differences by disaggregating data.

Looking Ahead

These findings add to the mounting evidence of persistent inequities in how postpartum depression is experienced, screened, and treated. Though screening is the first necessary step, it alone is far from sufficient. Systems must be responsive to the complex, intersecting challenges postpartum individuals face, especially those who have been historically marginalized. While awareness of PPD has grown, many of the people most in need—especially Black, Hispanic, low-income, and underserved birthing individuals—are still not being reached by the current system.

New York continues its efforts to understand, to address, and, ideally, to prevent the drivers of disparities, with the goal of providing equitable and effective maternal mental health care. As the United States faces an ongoing maternal health crisis—to which mental health conditions are a major contributor—the urgency of such efforts cannot be overstated.

Amy Ehntholt, ScD, is a Research Scientist at the New York State Office of Mental Health. She can be reached at Amy.Ehntholt@nyspi.columbia.edu.