Suicide is a public health crisis that demands our collective attention. Over the past two decades, while we have seen major forms of mortality like heart disease, stroke, and cancer decline, suicide rates have steadily increased both in the United States and New York State (NYS). Since 2000 the NYS suicide rate has climbed 40%. Each year, approximately 1700 New Yorkers die by suicide. These individuals are husbands, mothers, sons, sisters, friends, and coworkers. Consider also that each year, New York sees over 20,000 emergency department visits for self-harm; over half a million residents contemplate suicide and the approximately 147 individuals impacted for every 1 suicide and you see the scope of the problem.

Ann Sullivan, MD

Commissioner

NYS Office of Mental Health (OMH)

But there is good reason to have hope. Effective suicide prevention programs exist.

New York State has earned national recognition for its innovative work in suicide prevention and has one of the lowest (49th of 50) suicide rates in the nation (8.3/100,000 in 2018). The NYS Suicide Prevention Plan rests on three pillars: 1) integrating prevention into health and behavioral healthcare, 2) strengthening public health (non-clinical) prevention approaches at the community level, and 3) continuously improving the quality and timeliness of data used to guide comprehensive suicide prevention. We all have a role to play in advancing the NYS suicide prevention plan and creating suicide safer health systems, schools, and communities.

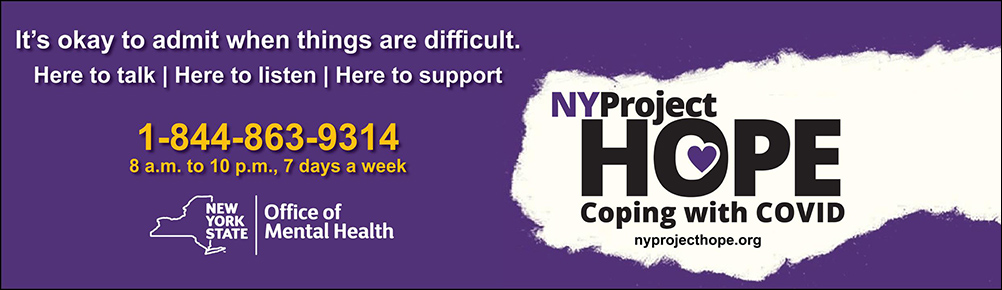

The arrival of COVID-19 has further highlighted the need to strengthen our suicide prevention efforts as well as the need to understand the unique cultural influences that impact the ways in which New Yorkers experience thoughts of suicide and engage with suicide prevention resources. The pandemic has disproportionally impacted communities of color and has exposed frontline workers to great stress. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a study in August outlining increased reports of anxiety, trauma, substance use, and serious thoughts of suicide during April – June 2020 as compared to the same time frame in 2019 (Czeisler 2020). NYS launched the Emotional Support Helpline in March, for those struggling to manage COVID-related stress and is continuing to support NY residents through Project Hope, targeted to provide support in the communities most impacted by COVID-19. In addition, the NY Cares media campaign is targeted to those suffering the economic impacts of the pandemic.

NYS Office of Mental Health (OMH) is also supporting suicide prevention training for an expected 6,000 New York City emergency medical personnel, designed to help them recognize distress in colleagues and the public who may be at risk for suicide. Governor Cuomo’s Suicide Prevention Task Force Report published in April 2019 acknowledged the need to consider “the unique cultural and societal factors that impact suicidal behavior” in order to improve programs and resources. Initiatives related to Task Force recommendations and beyond, designed to focus on the perspective and experiences of members of diverse and high-risk communities, have begun. Although interrupted due to the COVID-19 pandemic, OMH is continuing this important work virtually. From meeting with Latina adolescents and parents across the State to examine barriers to treatment and services; experts in the field of Black Youth Suicide Prevention to implement identified strategies, to convening rural suicide prevention experts and community members to focus on meaningful conversations such as “means safety”, OMH is committed to continually improving suicide prevention resources available to all New Yorkers. This fall a virtual summit on suicide prevention for veterans, law enforcement, corrections officers, and first responders is taking place and will include public presentations and strategy sessions of experts in suicide prevention from the specific populations.

In NYS’ war against suicide, behavioral health (BH) clinicians are frontline, essential workers. Regardless of setting—whether you are working at an inpatient psychiatric unit, community, or outpatient setting—and regardless of your discipline—whether you are a psychiatrist, peer counselor, or another BH practitioner—we all have a role to play in preventing suicide. Unfortunately, too often the training we receive in the assessment and management of suicide risk is inadequate. OMH has surveyed BH clinicians from a variety of settings and disciplines, and the findings are consistent: otherwise knowledgeable and skilled staff often do not feel confident in their ability to assess and manage suicide risk and want more training. To provide BH practitioners with the tools needed, OMH has partnered with the Center for Practice Innovations at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University to make a host of best practice trainings in suicide safer care available to BH clinicians in NYS. Suicide safer care should be part of the training curricula for all BH trainees and continue over the course of their careers.

A mainstay of the NYS approach (pillar 1) has been supporting health and behavioral health providers in integrating suicide prevention in their systems of care, often referred to as the Zero Suicide model. It is important to remember that even mental health systems have historically not been designed explicitly to reduce suicide deaths. Instead, they have evolved to deliver diagnostically driven services for individuals with mental illnesses, such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and borderline personality disorder, among others. Making that paradigm shift is central to the task at hand. The Zero Suicide model starts with a visible commitment from health system leadership to reduce suicide attempts and deaths among those receiving care, including investments in training clinicians in best practices and data driven quality improvement. The emphasis is moving to a system of care in which suicide safer care is consistently practiced, rather than counting on the heroic efforts of individual clinicians or crisis workers. The Zero Suicide model is both aspirational and practical. Provider systems are asked to systematically screen and assess suicide risk, provide evidence-based interventions, such as safety planning with means reduction, dialectical behavioral therapy, or cognitive therapy for suicide prevention, and to monitor between episodes of care, given the fluid nature of suicide risk.

Delivering high quality, high fidelity care is crucial in the Zero Suicide model. A cross-sectional study of 110 outpatient mental health clinics in NYS, the largest implementation of the Zero Suicide model in the nation, found fewer suicide attempts among clinics reporting greater fidelity to the Zero Suicide model. The literature also suggests that high quality safety plans done collaboratively with patients improve outcomes (reduced suicide attempts and hospitalizations) when compared to those of lower quality. Safety planning is a brief intervention that involves a prioritized list of strategies to help individuals cope with suicidal urges. It is critical to recognize safety planning as an intervention, rather than a form in vacuum. It is one thing for health systems to demonstrate that safety plans are being done with at-risk clients. It is something entirely different to show that those safety plans are being done well.

Transitional care is another essential component of suicide safer care. The immediate post-discharge is known to be a high-risk time for suicidal individuals. One recent meta-analysis suggested the risk of suicide for those leaving inpatient behavioral healthcare is 200-300 times higher than the general population and even higher in the first few days (Chung 2019). Closing this deadly gap must be a priority. But again, effective programs can reduce this risk. In a study involving veterans presenting to EDs for a suicidal crisis, safety planning with follow-up engagement in the immediate post-discharge period was associated with a 40% reduction in suicide attempts and a higher rate of following up with outpatient care (Stanley et al. 2018). In NYS the OMH Suicide Prevention Office has been working with hospital systems across the state as part of a federally funded Zero Suicide grant to ensure patients at elevated risk are engaged following inpatient and ED encounters until connected to community supports.

OMH is piloting a first in the nation program called Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program (ASSIP). ASSIP is a 3-session intervention for adults with a recent suicide attempt, a very high-risk group. The approach draws less on patient diagnosis and instead focuses on the patient’s unique story to develop a safety plan based on factors driving the recent suicide attempt. In one randomized controlled trial ASSIP reduced repeat suicide attempts by 80% (Gysin-Maillart 2016). ASSIP is now available for adults in Syracuse and Rochester.

It is important to note that peers have an important role to play in advancing the Zero Suicide model in NYS. Beyond advocacy and the power that comes with having peer support in clinical settings, demonstration projects are planned for in NYS around peer training in safety planning and providing follow-up support for at risk individuals discharged from EDs and those newly released from jail.

To “bend the suicide curve” in NYS suicide prevention efforts in health and behavioral healthcare systems must be complemented by public health approaches (pillar 2) at the community level. Perhaps the best example of a public health approach is NYS’ school-based prevention programs. In addition to being Suicide Prevention Month, September, of course, marks back to school. OMH continues to support robust school-based prevention in a number of ways, including expansion of school-based mental health clinics, development of a model school policy for preventing suicides, and providing a host of trainings for school staff. Over 21,000 school staff were trained since 2018 (see accompanying article on the next page by Dr. Jay Carruthers).

The third pillar of the NYS Suicide Prevention Plan is improving the accuracy, quality, and timeliness of the information used to guide our efforts across the state. While perhaps less visible then the work underway in healthcare systems, schools, and communities, sound data and surveillance are foundational. Without investments in this area, healthcare and community-based initiatives will not succeed. Surveillance data is crucial in recognizing populations at greater risk of suicide.

OMH is supporting an innovative program from Oregon in 4 NYS counties that highlights the power of robust community-level data leading to targeted interventions that save lives. The program has two main focal points: first, having medical death investigators capture key risk factors and circumstances data with every suicide death; second, assembling a group of community stakeholders, including law enforcement, healthcare providers, crisis workers and emergency medical services staff, to perform in-depth reviews of suicide deaths after obtaining consent from the legal next of kin. By allowing agencies to freely share information solely for the purpose of preventing future suicides, investigators were able to identify important trends in the data. One of the last things several decedents did, for example, was drop off their pets at animal shelters before killing themselves. Animal shelter staff have now been trained to recognize individuals at risk and connect them to supports and have already done so several times. By using the broader suicide fatality review model—a model driven by actionable community-specific data, Washington County, Oregon has been able to reduce its suicide rate by 40 percent. In NYS, we have already collected data on close to 200 deaths in the 4 pilot counties and in-depth reviews are underway.

Finally, one of the most important tools we have in the war against suicide is spreading stories of hope and healing, especially in the current media environment where we are flooded with discouraging news and statistics. Research supports this notion that positive media messaging involving real stories of people growing and working through suicidality can be protective. It even has a name—the Papageno effect, named after a character from a Mozart opera, who when contemplating suicide was swayed after shown more positive ways of resolving his problems.

Despite the rise in suicide rates, there are a number of ways for each of us to contribute to turning the tide and preventing suicides. Through our collective efforts we can make a difference, and New York State is leading the way. But we need All Hands on Deck!

If you are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting “Got5” to 741-741.