In these uncertain times of physical distancing, grievers are feeling more alone and isolated than ever. Many are craving physical closeness that is an integral part of the grieving process – a hug from a family member, lunch with a friend, someone dropping by to check on them.

Gillian Rittmaster, LCSW

The bereaved are missing “their person,” the loved one with whom they would have shared this experience, the days’ events, and their feelings. Grievers often have a sense of being unmoored and are now experiencing the loss of the anchor their loved one would have provided.

Grievers typically cope by keeping busy, filling their days with positive activities, and pushing through their grief. Now quarantined at home because of the Coronavirus pandemic, grievers are feeling the loss of this forward motion and describe feeling stuck and claustrophobic.

Trauma cannot be overlooked when we talk about loss during COVID-19. Many who have cared for a loved one are bearing the recurring thoughts and feelings that accompany witnessing a loved one suffer. During COVID-19, trauma and mourning have reached an unthinkable stage with loved ones barred from hospital rooms and stripped of rituals, such as funerals, wakes, and Shiva, which would have normally provided comfort and human connection.

The bereaved are also showing a tremendous amount of resilience during this unsettled time. They are drawing on their past experiences and coping skills to find the strengths that have worked well for them. Grievers gain strength not only by getting but by giving as well; some are volunteering to bring food to the homebound elderly and others are supporting their peers through online grief groups.

What these grievers have experienced and witnessed is unprecedented and they need a safe and validating space to talk about sadness, anger, loneliness, trauma, and above all, the story of their loved one. As clinicians we need to provide this holding space for our clients and not push them away from gruesome details so integral to their narrative. How do we do this when the work is so emotional, sad, and overwhelming? Clinicians are no strangers to loss, which makes bereavement work so challenging. All of us have or will lose someone we love in our lifetime. As clinicians we have to understand our own grief story. Who have we lost and how has it affected us? What themes of loss will you bring to the therapeutic relationship that will be helpful to the client? Is there a loss in the past or present that is holding you back from effectively supporting your client? One thing that is helpful to keep in mind is that bereavement is not a diagnosis; it is a human condition that we share with our clients.

The client’s story of the life and death of his or her loved one is more important than ever during these scary and unsettling times. Were they caring for a loved one at home whose condition worsened? Did their loved one die in the hospital alone? What did the client witness? Every client should be given the space to tell this story, as therapy may be his or her only safe space, and the clinician may be the only one willing to listen. The client may want to tell the story over and over again with each time new themes emerging. Clinicians will be able to help clients pick the bright spots out of the grim details pointing out resilience and strengths.

Clients need to tell not only the story of their loved one’s death, but their life as well. Who were they and what did they mean to others? How will their legacy live on? Clients will need to examine what role they played in their loved one’s life and who will they be now without them? As Isak Dinesen said “All sorrows can be born if you put them in a story or tell a story about them. When loss is a story there is no right or wrong way to grieve. There is no pressure to move on. There is no shame in intensity or duration. Sadness, regret, confusion, yearning and all the experiences of grief become part of the narrative of love for the one who died.”

In our role as clinicians we need to help clients integrate the grief into their life and learn how to hold both loss and hope, all while keeping a connection to the deceased. There are many assumptions and myths surrounding grief that we, and our clients hold as truth. One myth is that grief is about letting go, detachment and closure. Clients seek to close the hole in their heart their loved one has left, but instead realize over time that hole remains. The person has died, but the love, the memories and the relationship lives on. Grief is in fact about holding on and letting go. As clinicians we can help the client navigate holding both these feelings of loss and renewal. What will be the continuing bond that allows the client to carry their loved one with them? Will they wear an item of their clothing? Will they visit their grave or talk to them daily? Will they create legacy as they share stories with the next generation? Much of the work in mourning can be about how the person wants to construct this ongoing relationship, but not everyone will want to, as these continuing bonds are both comforting and painful. If grief is not about closure it is about finding and maintaining these continuing bonds.

During the quarantine it is particularly difficult to help clients “move forward” as forward motion has literally stopped across the globe. Clients describe now feeling alone in their grief, stuck at home with nothing but their photographs and memories, feeling disconnected from the support they need. As clinicians we can help clients add something to their grief so they can begin to hold both the loss and renewal. Can a client access what brings them peace and comfort? Is it talking to a friend who understands, listening to comforting music, doing something artistic or athletic, taking a long hot bath, watching a favorite TV show? As clinicians we need to stress self-care for clients as well as guard them against self-judgment. Some clients will think if they let go of a little pain they are letting go of the person; nothing is farther from the truth.

As our client’s personal grief has been swallowed up by the collective grief the world is feeling, we can support our clients in their quest to create meaning and attain connection. If unable to go to their house of worship can they tune in virtually? Can they hold on-line gatherings with friends and relatives to share stories of loved ones? Is there a daily ritual that would connect them to their loved one? Can they create an online memorial book where people post their memories? Will they consider joining an online bereavement group to get peer support and share universal themes of grief? Would a gratitude exercise help clients to both express what they have lost and look at what they have retained as well? In the weeks, months, and years to come we will need not only to bear witness to our clients’ stories, but also hold the hope for them that life beyond tragedy is possible.

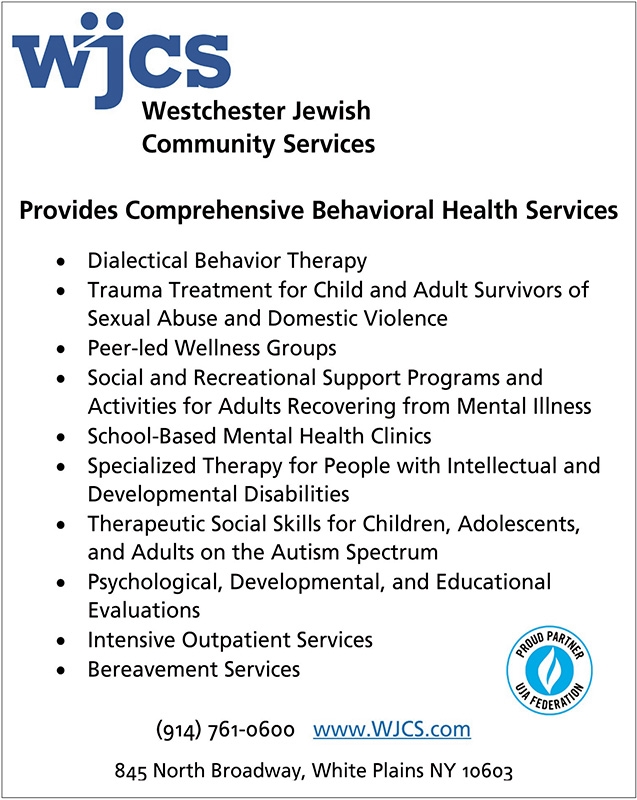

Gillian Rittmaster, LCSW, is Bereavement Coordinator for WJCS, one of the largest human service organizations in Westchester County, NY. WJCS offers individual and group bereavement support for Westchester County residents via telehealth for those who have suffered a loss of any kind.