For decades, much of the mental health field has operated under the assumption that certain individuals simply do not produce “enough” of a particular neurotransmitter, and that the most effective way to address this imbalance is through medication, supplemented by therapy focused on “coping” skills to help manage symptoms. But what if this view is incomplete? What if depression and anxiety are better understood through the lens of attachment theory and of the brain–body connection, considering how our physiological systems function and interact across the lifespan?

Medication and coping skills have undeniably proven helpful for many people experiencing depression and anxiety, particularly during times of crisis. However, there is often an implicit assumption that these approaches are the only options available. While it is important to recognize and value their role in stabilizing individuals in acute distress, it is equally important to challenge the belief that this is how it must “always be.” Such a perspective can be both limiting and, in many cases, inaccurate.

Development

Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development offers valuable insight into how individuals come to see themselves and the world around them. According to Erikson, the first developmental task of infancy is to establish trust: trust that caregivers will respond and provide care, trust that the world is safe and predictable, and trust in one’s own ability to have needs met. But what happens when this foundational task is left incomplete? When early experiences lead a person to believe that the world is not a trustworthy place, the consequences can echo across the lifespan. Individuals living with anxiety often struggle to accept that others can be trusted that the world is safe, and that they themselves are capable of meeting their own needs.

The remaining developmental tasks of childhood and adolescence also offer opportunities for anxiety and depressive symptoms to emerge, sometimes in ways that may appear “untreatable,” particularly when these symptoms are evident early in life. Although these stages focus on the individual’s growth, each requires meaningful engagement with a primary caregiver to be successfully navigated. This interdependence underscores the critical role of attachment and early relational experiences in shaping mental health outcomes across the lifespan.

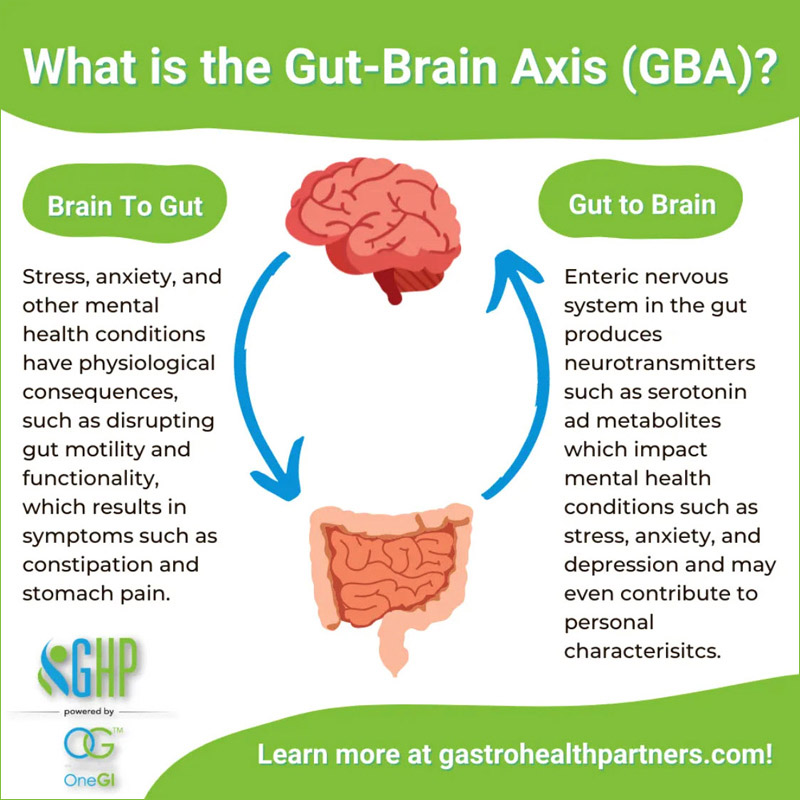

How does this connect back to medication, neurotransmitters, and our understanding of anxiety and depression? Historically, research has linked both conditions to imbalances in specific neurotransmitters, either too little or too much of a given chemical. However, it is short-sighted to assume that the brain and body operate in isolation. The two are in constant communication: what the brain perceives and believes influences the body’s chemical production, and what the body produces in turn affects mood, thought patterns, and emotional states.

The gut and brain are in constant communication, working together to help the body “know” and respond to what is happening. For example, the brain signals the gut when to begin digestion and when to stop. You may recall the old saying that constant worry can lead to ulcers, there’s truth to that. Chronic stress causes the stomach to release excess acid, and over time, this can overwhelm the gut.

Interestingly, about 80% of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gut. Serotonin plays two key roles: supporting digestion and regulating mood. Because the body prioritizes survival, serotonin is first directed toward digestion. This is why people who experience ongoing gut issues often also report symptoms of depression, the same chemical system that supports healthy digestion is closely tied to our sense of well-being.

Healing Old Wounds

There is encouraging news when it comes to healing old wounds. While emotional wounds are often the most difficult to address, they are also the ones that most deeply shape our beliefs about ourselves, others, and the world. Even though we cannot see these wounds, it is possible to heal them, often through the power of new, healthy relationships. Beyond the importance of our connections with others, our relationship with ourselves plays an equally vital role in this healing process.

Healing begins when we allow ourselves to be open to new experiences that challenge the narratives our wounds have created. Safe, nurturing relationships can offer corrective emotional experiences that help rewrite the messages of unworthiness, fear, or mistrust that may have taken root long ago. These new interactions, whether with friends, partners, mentors, or therapists, can provide evidence that our old beliefs no longer define us.

Equally essential is the internal work of developing self-compassion and self-trust (Greater Good Science Center). Our inner dialogue can either perpetuate old pain or pave the way toward renewal. By consciously choosing to speak to ourselves with kindness, set healthy boundaries, and honor our needs, we begin to restore the parts of ourselves that were once hurt. In doing so, we cultivate a relationship with ourselves that becomes a steady, supportive foundation, one that not only helps heal the past but also strengthens our ability to face the future with hope and resilience.

Practical Steps to Address Depression and Anxiety Using Attachment Theory

Here are a few actionable steps that you can take to address experiences of depression and anxiety:

- Identify healthy support people already in your life. If part of the reason that you are experiencing some of these symptoms is because of disrupted relationships in the past, it is helpful to notice and leverage the support people already in your life. (APA)

- Change your internal monologue. We believe what we hear, even if it is in our own head. If your internal monologue is consistently negative, we will believe those thoughts are “truth.” However, thoughts like “I am a complete and utter failure” or “I cannot do anything right” are not rational and they are not truth. Challenging and replacing thoughts is an important step in addressing difficulties.

- Notice your body and care for it. Taking good care of your body requires healthy food, enough water, enough rest, a reduction in stress, and exercise or movement. Our body impacts our mood, and our mood impacts our body! (Harvard)

Conclusion

Too often, we assume that how things are right now is how they have always been—and how they will always be. But that simply isn’t true. The body is a system, and when one-part changes, the others inevitably adapt. When we view our body, mind, and spirit as a unified whole rather than separate parts, we open the door to new and creative ways of managing life’s challenges. In that integration lies the possibility of renewal, and the restoration of hope where it may have long been lost.

Dr. Vicki Sanders, LMFT 52610 runs a group private practice in Fresno, CA. Contact her at www.drvickisanders.com or via email vicki@vmsfamilycs.com.