More and more today, mental health care is accepted as an optimal course of action for millions of people. Those seeking care anticipate restorative outcomes. As recently as thirty years ago, mental health institutions were referred to in derogatory terms. Many of these secure institutional facilities at that time were created for patients who would end up staying indefinitely due to the inability to obtain approval for release. Today, we refer to these facilities as mental and behavioral health facilities, psychiatric hospitals, outpatient treatment centers, or crisis centers – to name a few – depending on the facility’s intended operation and its clients’ treatment needs. Over time, a stigma has been attached to the abusive mental health practices used up until 1967, when the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act of 1967, ended the practice of institutionalizing patients against their will. As asylums closed across the U.S. between 1967 and 1994, the justice system began to inherit portions of the population with mental health or behavioral health needs. Due to inability to find proper placement or treatment facilities, detention centers were slowly becoming the largest mental health institutions.

To challenge the status quo, reviewing and changing terminology is necessary to bring dignity, health, and wellness to patient care, to remove barriers from access to care, and to give better understanding to evidence-based practices and treatment. Updated facility language does not only exist to remove derogatory connotations, but it also shifts to align with modern, best-practice approaches for mental or behavioral healthcare that emphasize providing patients with the self-confidence and active role in their treatment towards recovery and stability. With the foundation of correct terminology, results include improved treatment descriptions, room names, wayfinding that eases stress, and facility names that are inviting versus anxiety-inducing. These improvements allow a much healthier and normative environment. Cumulatively, there is one goal in mind: the successful treatment of the patient or client and to destigmatize and decriminalize mental and behavioral health.

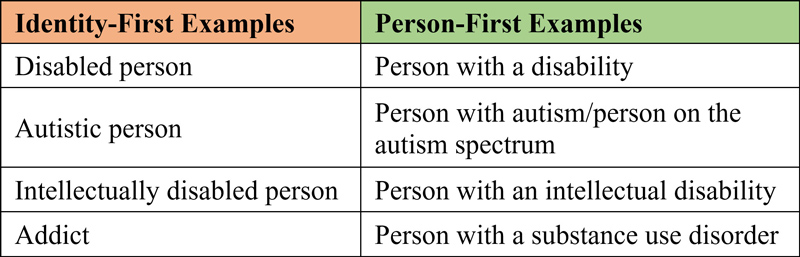

Person-First Versus Identity-First Language

Language updates also apply to how we refer to individuals with mental or behavioral health needs. Our industry is shifting to focus on using person-first language, which is a linguistic approach that puts a person before a diagnosis. Identity-first language describes a person in the context of a disability, medical condition, or cognitive difference. In the past, an identity-first language example would be calling a person “a schizophrenic,” whereas in the push for change to de-stigmatizing person-first language today, this person would be described as an “individual who lives with schizophrenia.” These simple but important updates to language allow us to avoid identifying or defining patients by their condition. Each patient is valued and should be spoken to with dignity.

Currently, there is no legislated change for terminology or standardized terminology across the industry for conditions or patients. We must choose to be proactive in the use of a person-first terminology. To help foster positive change in the design industry, the focus must shift towards creating equality and equity within design, including how spaces are formed, how they are named and operated, and how operations and occupants are described. In doing so, designers can bring respect and dignity to patients, clients, and staff. This movement removes barriers when accessing care and lessens patient and client anxiety in the overall process. It helps support the paradigm shift from, “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you and how can we help?”

Examples are taken from thesaurus.com

Designing a Welcoming Patient/Client Experience

To coincide with updates in healthcare language, architecture and interior design professionals are updating the way they design mental and behavioral health facilities. One primary area of focus is implementing clear and inviting interior, exterior, and wayfinding signage. Designers should work to consider the sensory reaction to a space. Typically, people experiencing mental or behavioral health issues are either hyper-sensitive to their environment or have sensory impairment. Design considerations are important, such as how welcoming each space is, what the path of travel from the parking lot to the reception area looks like, the design of corridor circulation, and dignity/privacy versus security and safety within patient rooms. Designers can employ several design strategies to make patients and clients feel welcome, including:

- Normalized ligature-resistant furniture, fixtures, and equipment

- Appropriate acoustics in all facility spaces

- Warm, natural, and stress-reducing materials and finishes that can be easily sanitized

- Expansive windows/daylighting

- Connection to nature, including gardens, walking paths, and natural features

- LED lighting with options for individualized control/circadian rhythm programming

Additionally, one growing design innovation is to create sensory spaces for patients and staff to relax and decompress or proactively excuse themselves. These spaces are used for mindfulness, not for isolation or punitive institutional actions. Sensory spaces typically have soothing colors, artwork, comfortable furniture or materials, changeable light settings and colors, music, and some include water soundtracks or monitors with guided decompression or breathing exercises.

Embracing the Approach in a New Facility

Our team is currently designing the New Psychiatric Hospital in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which will be a leading crisis center in the area. The Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services is embracing a design approach that reduces the stigma surrounding mental health. This facility is being designed so that spaces feel warm and welcoming for their patients. Ideally, as patients become more comfortable and trusting of their environment, they will open more fully to their treatment plans and actions.

Rethinking the Way We Think and Communicate About Healthcare

The U.S. mental or behavioral healthcare system is slowly adapting to the modern world, but there is still much to be done. Changing how we look at mental health and behavioral health patients, updating our language and terminology, and improving our design strategies will have a profound impact on both the patient/client experience and their recovery process. When we speak with dignity for others, we offer them respect and value and support our vulnerable populations.

Brooke Martin, AIA, NCARB, CCHP, LEED Green Associate, an associate and project manager based in Dewberry’s Peoria, Illinois, office, has 17 years of experience. She has a passion for justice architecture, and focuses on supportive, trauma-informed, intentionally humane design that supports positive, treatment-focused outcomes within skill-building and learning environments and integrating functions that fit within a community’s continuum-of-care. Martin can be reached at bmartin@dewberry.com.

Cassey Franco, AIA, LEED AP, is a senior architect based in Dewberry’s Tulsa, Oklahoma, office, has nearly 30 years of experience in design of healthcare facilities. She works to bring functionality, constructability, and aesthetics to her projects and has a passion for implementing transformative designs for restorative outcomes. Franco can be reached at cfranco@dewberry.com.

For more information, visit www.dewberry.com.

References

2021, Person-First Language vs. Identity-First Language: Which Should You Use?

www.thesaurus.com/e/writing/person-first-vs-identity-first-language/