For decades, systemic racism has disproportionately routed Black and Brown children who have unmet behavioral health needs to congregate care and residential programs, and adults with these needs, to jails and prisons (Bronson & Berzofsky, 2017; National Conference of State Legislatures, 2021). Trauma is both a key driver and a compounding factor. Providers have grown accustomed to treating behavioral health needs that are both rooted in and buried by systemic disparities. Yet, many of those who have the greatest needs are not served by the delivery system we have today. We knew this before COVID further exposed the deep fissures in our systems.

The statistics are stark. Nearly 1 in 5 children and 1 out of 5 adults have a mental, emotional, or behavioral disorder, yet only about 20% of children who need services receive care from a specialized mental health care provider and only 65% of adults who have a serious mental illness receive mental health services (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), 2018; Martini et al., 2012; National Institute of Mental Health, 2021; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009). Black and Brown populations face the most extreme barriers: Over 50% of Latinx young adults ages 18-25 who have a serious mental illness do not receive treatment (Mental Health America, n.d.; National Alliance on Mental Illness, n.d.). The rate is the same for Black and African American young adults ages 26-49 with a serious mental illness, but it climbs to 58.2% for those aged 18-25 (Artiga et al., 2020). In addition, a staggering 90% of Black and African Americans with a substance use disorder do not get care at all (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2019). In 2018, 11.5 percent of Black and African Americans, versus 7.5 percent of White Americans, were still uninsured, despite the Affordable Care Act, and even those who can access services often receive treatment that is ineffective or inadequate (CDC, 2019; CMS, 2018; Frueh, 2009).

Trauma is a deep undercurrent. Children who experience trauma are at high risk for long term problems associated with mental health and physical health as well as problems related to socialization and quality of life (Hills et al., 2004). Experiencing trauma contributes to the development of severe mental illness (SMI) and individuals with SMI are at greater risk for PTSD and other negative impacts of traumatic experiences (Goodman et al., 2001). While targeted treatment, evidence-based practices, and social supports can contribute to positive outcomes, these services continue to be inaccessible to far too many people due disparities in the system.

We are in a pivotal moment in building an equitable behavioral health system that can effectively address trauma (Grape et al., 2014). We know the needs, and now the resources are available. In addition to the American Rescue Act, New York State is preparing for its long-anticipated waiver renewal.

We have a long way to go, but this is the time to start implementing the approaches we already know work for those who need care the most. Providers and community-based organizations must play an active role in establishing what outcomes have value, with an active focus on systemic change. Targeted outreach, community engagement, and services that align with the principles of trauma-informed care and are coordinated within integrated networks offer a blueprint. For example:

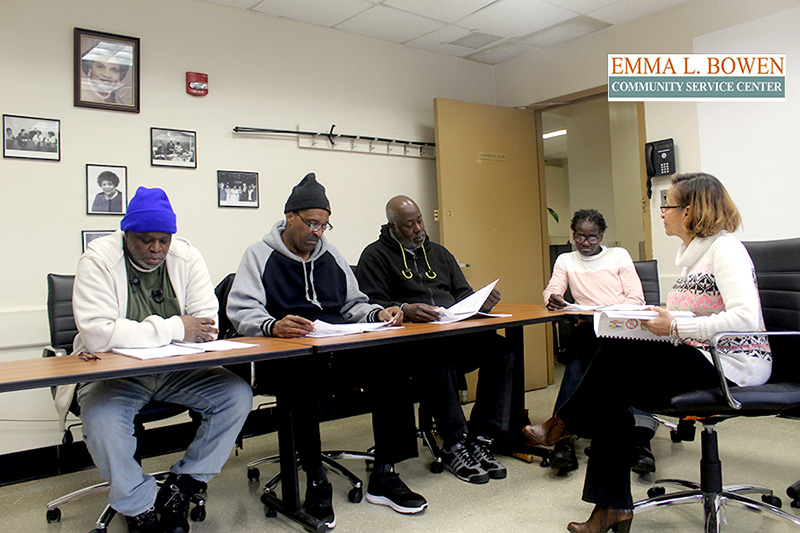

The Emma L Bowen Community Service Center (BowenCSC) aka Upper Manhattan Mental Health Center, a behavioral health provider in West Harlem, has developed a network of community-based and faith-based organizations to promote trauma and mental health awareness, offer community-based support, identify those in need of formal intervention, and create new access points for treatment in its Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic (CCBHC) program. By leveraging the entities already reaching those who remain outside of the BH system and need a pathway “in”, BowenCSC has established a community-wide trauma response for outreach, screening, and engagement of Black and Latinx children, youth, and their families in the Upper Manhattan and South Bronx communities. With support from Adelphi University, they are addressing the community’s double jeopardy of pre-pandemic vulnerabilities and pandemic-exaggerated disparities by supporting partners to expand screening using the UCLA Brief COVID-19 Screen for Child/Adolescent PTSD and engaging a Certified Recovery Peer Advocate (CRPA) to offer the Attachment, Regulation, and Competency (ARC) and Trauma-Adapted Family Connections (TA-FC) approaches. While fortifying its existing network, BowenCSC is also further expanding the organizations able to screen and referral community members to behavioral health treatment, as well as establishing virtual telehealth sites to improve access. Recognizing the heightened value of early intervention, BowenCSC has also modified its scope of practice to enable treatment of co-occurring disorders beginning at age 12, and is participating in the Mayor’s initiative to expand the membership and rehabilitative reach of the Clubhouse model to promote sustainable supports in the community.

Bowen Center Tobacco Cessation Group

Another highlight: Coordinated Behavioral Health Services (CBHS), an integrated network of behavioral health and community-based providers in the Hudson Valley, has initiated a process to develop trauma-informed standards of care, informed by the values of social justice and anti-racism. This initiative is being led by representatives from CBHS’ two dozen member agencies, including Pat Lemp, Chief Clinical Officer of Westchester Jewish Community Services and Susan Miller, Vice President, Hudson Valley Services, of Rehabilitation Support Services, Inc. They co-chair a CBHS Trauma Informed Care (TIC) committee that includes diverse membership from the CBHS membership, which includes both clinical and non-clinical treatment and recovery support providers. The TIC committee has embedded the principles of TIC in the development of the standards of care and an attestation process to reinforce the commitment to TIC throughout the network. The TIC subcommittee recognizes that providers are at different places in the development of trauma-informed cultures and that TIC is not an endpoint but an ongoing process of growth and learning. The TIC committee is laying the foundation to provide the support and resources needed by the complex and vulnerable populations CBHS seeks to better serve by ensuring that TIC, with an intentional focus on racial justice, is woven into the delivery of all essential services and that robust community partnerships facilitate access to care.

These examples demonstrate how addressing trauma and racial disparities at the community level provides the opportunity to advance healing for individuals while also building the community infrastructure needed to support resilience and change the trajectory of social relationships and connections (Pinderhughes et al., 2015). When planning includes the application of a trauma lens, there is the potential for long term impact. For these new models to work, government and payors must advance alternate payment models that centralize health equity and continue to allow providers the regulatory flexibility that innovation demands (Klinenberg, 2018). This is time for power sharing and collaboration in the interest of optimal outcomes. By mobilizing community assets to promote access and realize the cost saving economies of effective care, we can achieve the behavioral health system we have needed all along.

About the Authors: Heidi Arthur, LMSW, Principal, Health Management Associates. Catherine Guerrero, MPA, Principal, Health Management Associates. Lawrence Fowler, Deputy Executive Director, The Emma L. Bowen Community Service Center. And Mark Sasvary, PhD, LCSW, Chief Clinical Officer, Coordinated Behavioral Health Services.

References

Artiga, S., Orgera, K., & Damico, A. (2020). Changes in health coverage by race and ethnicity since the ACA, 2010-2018. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-since-the-aca-2010-2018/

Bronson, J. & Berzofsky, M. (2017). Indicators of mental health problems reported by prisoners and jail inmates, 2011-12 (NCJ 250612). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/imhprpji1112.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Tables of summary health statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/shs/tables.htm

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2018). CMS announces new Medicaid demonstration opportunity to expand mental health treatment services. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-announces-new-medicaid-demonstration-opportunity-expand-mental-health-treatment-services

Frueh, B. C., Grubaugh, A. L., Cusack, K. J., & Elhai, J. D. (2009). Disseminating evidence-based practices for adults with PTSD and severe mental illness in public-sector mental health agencies. Behav Modif. 33(1), 66-81. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2702227/.DOI: 10.1177/0145445508322619

Goodman, L.A., Salyers, M.P., Mueser, K.T., Rosenberg, S.D., Swartz, M., Essock, S.M., Osher, F.C., Butterfield, M.I., & Swanson, J. (2001). Recent victimization in women and men with severe mental illness: Prevalence and correlates. J Trauma Stress. 14(4), 615-632. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11776413/. DOI: 10.1023/A:1013026318450

Grape, A., Plum, K.C., & Fielding, S. (2013). Disparity of SED recovery: Community initiatives to enhance a system of care mental health transformation. Journal of Applied Social Science. 8(1), 8–23. www.jstor.org/stable/43615182.

Hills, S. D., Anda, R. F., Dube, S., Felitti, V. J., Marchbanks, P. A., & Marks, J. S. (2004). The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics, 113(2), 320-327. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14754944/.DOI: 10.1542/peds.113.2.320

Klinenberg, E. (2018). Palaces for the people: How social infrastructure can help fight inequality, polarization, and the decline of civic life. Crown.

Martini, R., Hilt, R., Marx, L., Chenven, M., Naylor, M., Sarvet, B., Kroeger, K. (2012). Best principles for integration of child psychiatry into the pediatric health home. https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/clinical_practice_center/systems_of_care/best_principles_for_integration_of_child_psychiatry_into_the_pediatric_health_home_2012.pdf

Mental Health America (MHA). (n.d.). Racial trauma. https://www.mhanational.org/racial-trauma

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). (n.d.). Hispanic/Latinx. https://www.nami.org/Your-Journey/Identity-and-Cultural-Dimensions/Hispanic-Latinx#:~:text=Hispanic%2FLatinx%20communities%20show%20similar,illness%20may%20not%20receive%20treatment.22

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2021). Racial disproportionality and disparity in child welfare. https://www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/disproportionality-and-race-equity-in-child-welfare.aspx

National Institute of Mental Health. (2021). Mental illness. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2009). Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Washington (DC): National Academic Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK32775/. DOI: 10.17226/12480

Pinderhughes, H., Davis, R.A., & Williams, M. (2015). Adverse community experiences and resilience: A framework for addressing and preventing community trauma. Kaiser Permanente. Prevention Institute, Oakland CA. https://www.preventioninstitute.org/sites/default/files/publications/Adverse%20Community%20Experiences%20and%20Resilience.pdf